OK. Here is what we know:

1. Tyrone Woods, 41, and Glen Doherty, 42 - The stand these men made at Bengazi was like the one at the Alamo. They knew they were outnumbered with limited ammo but stood on the line.

I know that the Arabs paid dearly for every inch of territory between them and the ambassador before they were overrun. God Bless them, their families, and may they find peace now that they have been called home.

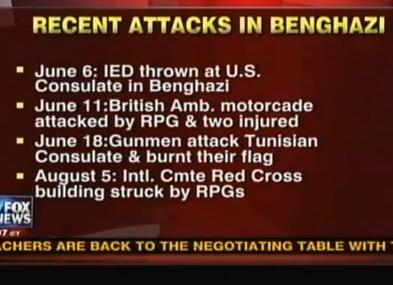

2. There were four previous Islamist attacks in Benghazi since June.

One of the attacks was an IED atack at the US Consulate on June 6, 2012.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=1RwVC186ygE

Yet, the Obama Administration refused to provide even “standard security” at the consulate compound.

3. Worldwide Protective Services (WPS) contract:

The WPS contract has a maximum value of $10 billion for all task orders combined, including one base year and four 1-year options. So, the Administration stating money was the problem is a red herring.

Money cuts are a problem but the main one is relying on contractors and not U.S. Marines.

On WEPs , the technical merit factor included four sub-factors: personnel staffing, recruitment, screening/vetting, and retention; training; program and logistics management; and risk management and mitigation. The WPS contract solicitation stated that the contract was to be awarded as a "best value" to the Government rather than to the lowest priced proposal. 14 FAH-2 H-361(b)1

(However, as offers become technically equivalent, cost or price may become the determining selection factor.) So, contracted embassies are guarded by the lowest bidder. Great.

The eight contractors awarded the WPS contract on September 29, 2010, were the following:

Aegis Defense Services, LLC

SOC, LLC

International Development Solutions, LLC

Torres International Services, LLC

EODT

Triple Canopy, Inc.

Global Strategies Group, Inc.

DynCorp International, LLC

Private firms generally lack transparency to outsiders, regardless of their industry. Some of this is a systematic side- effect of being private, not the result of deliberate policy. After all, they are not required to be transparent, and they have no reason to be. If most PMFs are private, then one would expect the industry to lack transparency, regardless of its activity type.

Capabilities are important because underlying contracts (transactions in the marketplace) are firm-level capabilities. The concept of capabilities is widely used for analysis in the strategic management literature because it focuses on the building blocks for activities that are present in a firm (and, therefore, an industry sector). Firms distinguish themselves by their capabilities—firms are able to get contracts others cannot access because they can either do things other firms cannot do, or they can do them at a lower cost than their competitors.

http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=the%20Diplomat's SecurityWhy has Senator McCaskill from

As the Chairman on WEPs Contracts she knows of the problems in their use.

The Committee also detailed evidence of serious misconduct by EODT in Afghanistan, including: Relying on local Taliban warlords to provide guards and, in some cases weapons, for use on EODT's contracts; Failing to adequately investigate guards' previous employment, which resulted in the company's hiring individuals who had previously been fired for sharing sensitive security infonnation with Taliban warlords; and Failure to appropriately vet guards, some of whom, according to U.S. intelligence reports, may have been involved in anti·American activities.

Could it be that the guards in

Yet, no one in the Obama administration is stepping forward. No they are ducking for cover by lying to the American People.

In January 2008, Claire McCaskill decided to endorse Senator Barack Obama in his campaign for the Democratic nomination for the presidential elections of 2008, making her one of the first senators to do so. She has been one of the most visible faces for his campaign.[10] McCaskill's support was crucial to Obama's narrow victory in the

Why has Senator McCaskill from

Letter From the Chairman of the Subcommittee on Contracting Oversight,

By Josh Rogin | Friday, September 28, 2012 | Foreign Policy

The mother of Tyrone Woods, one of the two former Navy SEALs killed in the Sept. 11 attack on the Benghazi consulate, is speaking out about the slow pace of the investigation into the death of her son and three other Americans.

"Don't want to ever politicize the loss of my son in Libya, but it has been 16 days and the FBI has yet to get to Benghazi to begin their investigation," Woods's mother Cheryl Croft Bennett wrote on her Facebook page Thursday. "Apparently they have made it to Tripoli but haven't been allowed to enter Benghazi. Meanwhile, the diplomatic outpost where Tyrone and [former SEAL] Glen [Doherty] died, was not and is not secured. Absolutely unacceptable."

Read more: http://nation.foxnews.com/us-embassy-attack/2012/09/28/murdered-ex-seals-mother-frustrated-pace-benghazi-investigation#ixzz27xksNiqs

The Scorpion And The Frog

Aesop’s fable, The Scorpion and the Frog, illustrates the “Obama Doctrine” in the volatile Middle East and North African Muslim countries.

The Scorpion and the Frog

A scorpion and a frog meet on the bank of a stream and thescorpion asks the frog to carry him across on its back.

The frog asks, “How do I know you won’t sting me?” The scorpion

says, “Because if I do, I will die too.”

The frog is satisfied, and they set out, but in midstream,

the scorpion stings the frog. The frog feels the onset

of paralysis and starts to sink, knowing they both will

drown, but has just enough time to gasp “Why?”

Replies the scorpion: “Its my nature…”

Mollie Hemingway wondered if anything the Obama administration said about Benghazi was true. She ended her post with this quote from the CBS report.

"What's clear is that the public won't get a detailed account of what happened until after the election."Well this is not detailed information, but it is a fact well worth knowing.

The two former SEALS, Tyrone Woods, 41, and Glen Doherty, 42, were not employed by the State Department diplomatic security office and instead were what is known as personal service contractors who had other duties related to security, the officials said.And to it, add this account from the funeral of one of those heroes as reported on blackfive, by someone who is was a member of the SEAL community, and attended the final farewell.

The two ex-Seals and others engaged in a lengthy firefight with the extremists who attacked the compound, a fight that stretched from the inner area of the consulate to an outside annex and a nearby safe house -- a location that the insurgents appeared to know about, the officials said.

Excerpted from Froggy’s piece in BlackFive: Ty and Glen Doherty are former SEALs and State Department contractors who came to the aid of the US Ambassador to Libya during the attack on the Benghazi Consulate.“To all the Operators here today I give you this charge: Rid the world of those savages. I’ll say it again, RID THE WORLD OF THOSE SAVAGES!”

Ty’s widow, Dorothy, delivered an inspiring eulogy with more grace, poise, and fervor than I have ever witnessed from the spouse of a fallen warrior. I wish I had the entire thing on tape, as it should be read by the nation on the anniversary of 9/11 next year. Here are two quotes that I will never forget.

“It is easy to write a book about being a Navy SEAL, but it is very hard to write an obituary for one.”

Mike Ritland interview was, very poignant, respectful, and a reflection of Mike's grief and ability to handle a nation-wide interview like handling a chat between two respectful war vets.

The interview is in video. If eating too much bandwith, then please delete. But take my word for it, Mike showed class, even when at the end he said "My pleasure".

Special Forces ›

U.S. officials clarify administration description of two heroes in Libya attack

The interview is in video. If eating too much bandwith, then please delete. But take my word for it, Mike showed class, even when at the end he said "My pleasure".

Special Forces ›

U.S. officials clarify administration description of two heroes in Libya attack

Ex-Navy Seals weren't part of ambassador's security detail but rose to occasion, officials now confirm

Why It Matters:

The Obama administration's initial account of the Libyan consulate attack didn't give the full story about two ex-Navy SEALs who helped repel the security breach until they were killed. Now officials are confirming those two heroes' real jobs at the embassy along with evidence of ties between the attack and al-Qaida.

The two former Navy SEALs killed in last week's attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi were not part of Ambassador Chris Stevens' official security detail but took up arms in an effort to protect the facility when it was overrun by insurgents, U.S. officials tell the Washington Guardian.

The two former SEALS, Tyrone Woods, 41, and Glen Doherty, 42, were not employed by the State Department diplomatic security office and instead were what is known as personal service contractors who had other duties related to security, the officials said.

They stepped into action, however, when Stevens became separated from the small security detail normally assigned to protect him when he traveled from the more fortified embassy in Tripoli to Benghazi, the officials said.

The two ex-Seals and others engaged in a lengthy firefight with the extremists who attacked the compound, a fight that stretched from the inner area of the consulate to an outside annex and a nearby safe house -- a location that the insurgents appeared to know about, the officials said.

The officials provided the information to the Washington Guardian, saying they feared the Obama administration’s scant description of the episode left a misimpression that the two ex-Navy SEALs might have been responsible for the ambassador’s personal safety or become separated from him.

“Woods and Doherty weren’t part of the detail, nor were they personally responsible for the ambassador’s security, but they stepped into the breach when the attacks occurred and their actions saved others lives -- and they shouldn’t be lumped in with the security detail,” one senior official said, speaking only on condition of anonymity because he wasn’t authorized to speak publicly about the State Department.

The administration has not fully described the two former Navy SEALs' activities, characterizing their work only vaguely as being security related. “Our embassies could not carry on our critical work around the world without the service and sacrifice of brave people like Tyrone and Glen," Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said after the attacks.

As recently as Sunday, UN Ambassador Susan Rice gave a similar description. “Two of the four Americans who were killed were there providing security. That was their function. And indeed, there were many other colleagues who were doing the same with them,” Rice told ABC's This Week program.

In fact, officials said, the two men were personal service contractors whose official function was described as "embassy security," but whose work did not involve personal protection of the ambassador or perimeter security of the compound.

The details emerged the same day that U.S. officials confirmed in public a Washington Guardian story Friday that U.S. intelligence believes al-Qaida or its affiliates played a role in the attack. "We are looking at indications that individuals involved in the attack may have had connections to Al Qaeda or Al Qaeda's affiliates," Matt Olsen, the director of the National Counterrorism Center, told lawmakers.

Administration officials had downplayed al-Qaida connections shortly after the attack.

Many U.S. agencies in foreign hotspots like Benghazi rely on and even share contract workers with special skills like those of retired Navy SEALs for security, reconnaissance and threat assessments.

Unlike full embassies such as the one in Tripoli, consulates like Benghazi usually don’t have a contingent of Marines to provide security, and private contractors help fulfill some of those responsibilities. The Washington Guardian reported last week concerns about the embassy security that predated the deadly attack.

Those briefed on the latest intelligence say investigators are trying to determine when and why Stevens’ official State Department security team got separated from the ambassador when the attacks occurred the evening of Sept. 11.

The separation of the team from the ambassador remains one of the more serious matters under review, the officials said.

In addition, while the administration has downplayed any link to al-Qaida, there is evidence some of the attackers were affiliated with another group that sympathizes with al-Qaida and has grown more influential in Libya and other parts of north Africa.

State Department officials did not respond to emails or phone calls seeking comment Wednesday.

The current evidence leads U.S. intelligence to believe that a band of Islamist extremists with some ties to the north African affiliate of al-Qaida had accumulated a stash of weapons and extra human muscle, performed some reconnaissance to identify possible U.S. targets, and may have even infiltrated the Libyan security forces that help protect the consulate in hopes of eventually conducting a terrorist operation somewhere in Benghazi.

However, U.S. intelligence does not believe -- at present -- that the attackers specifically targeted Stevens, official said. Instead, they think the attackers sprang into action when, seeing crowds forming outside the consulate on Sept. 11, they perceived an opportunity to carry out a terrorist attack, officials said.

“Yes, they were killed in a terrorist attack on our embassy,” Olsen told the Senate Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee on Wednesday. “The best information we have now, the facts that we have now, indicates an opportunistic attack on our embassy.”

U.S. officials say they have some evidence at least one of the attackers had prior connections to al-Qaida's senior leadership and that others were linked to a sympathetic spinoff group in northern Africa known as al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, which is gaining influence in Libya.

Specifically, U.S. intelligence is investigating whether there is any connection to an al-Qaida-linked player named Sufyan Ben Qumu, who was captured by U.S. officials after the September 11, 2001 attacks and held at Guantanamo Bay for years before being released to Libyan authorities by the Bush administration in 2007. Qumu has emerged in recent months as an increasingly influential Islamist figure in eastern Libya, near Benghazi.

Fox News reported Wednesday night he might be a mastermind of the attack, but U.S. intelligence officials said such conclusions are premature.

“There’s an active effort to uncover those individuals and groups who were responsible for the attack. Any suggestion that a leading suspect or ‘mastermind’ of the attack has been identified at this point is premature. It is safe to assume that any significant extremist in Eastern Libya is going to be under a lot of scrutiny right now," one U.S. intelligence official told the Washington Guardian.

U.S. intelligence believes part of the motivation for launching the attack was a video from al-Qaida leader Ayman al-Zawahiri that surfaced the night of Sept. 10, imploring Libyans to attack Americans in retribution for the U.S. drone strike that killed Libyan-born al-Qaida leader Abu Yahya al-Libi in June.

The Washington Guardian reported on Friday that U.S. intelligence had intercepted and translated Zawahiri’s message imploring Libyans to attack U.S. officials the night before the consulate attack and were still analyzing its significance when the ambassador was killed. No significant changes to security countermeasures at the diplomatic mission were taken until after the compound was overrun.

The White House claims two ex-SEALs killed in Libya were inept security guards. The truth? They volunteered for duty and died heroes. But that doesn't serve an Obama political purpose, now does it?

According to the Obama administration's United Nations ambassador, Susan Rice, the two former Navy SEALs who died defending the Benghazi consulate from attack this month, Tyrone Woods, 41, and Glen Doherty, 42, were State Department employees on the consulate's security detail when they somehow got overpowered by a mob that was enraged by an anti-Islamic film.

That's questionable, given that the consulate endured a sustained paramilitary-style attack that left the consulate aflame, killed U.S. ambassador Chris Stevens and diplomat Sean Smith, and ended with a desperate trail of bloody handprints across the consulate walls.

"Tragically, two of the four Americans who were killed were there providing security. That was their function," Rice told ABC News' Jake Tapper in an interview earlier this week.

Hold on. It now comes to light that they weren't State Department employees and they weren't there to protect the consulate. They bravely did it on their own.

In reality, they were two contractors working on a separate mission — with at least one tracking down missing shoulder-fired missiles, according to ABC News.

"Woods and Doherty weren't part of the detail, nor were they personally responsible for the ambassador's security, but they stepped into the breach when the attacks occurred and their actions saved the lives of others," an unnamed U.S. official told the Washington Guardian.

So as the consulate was pummeled with mortar fire from an organized al-Qaida terrorist attack, the two men, with no preparation and no ground intelligence, just plain stepped forward without any obligation to do so, and died defending the U.S. after the non-U.S. contractors who were paid to do that ran away.

The two former SEALS, Tyrone Woods, 41, and Glen Doherty, 42, were not employed by the State Department diplomatic security office and instead were what is known as personal service contractors who had other duties related to security, the officials said.

They stepped into action, however, when Stevens became separated from the small security detail normally assigned to protect him when he traveled from the more fortified embassy in Tripoli to Benghazi, the officials said.

The two ex-Seals and others engaged in a lengthy firefight with the extremists who attacked the compound, a fight that stretched from the inner area of the consulate to an outside annex and a nearby safe house -- a location that the insurgents appeared to know about, the officials said.

The officials provided the information to the Washington Guardian, saying they feared the Obama administration’s scant description of the episode left a misimpression that the two ex-Navy SEALs might have been responsible for the ambassador’s personal safety or become separated from him.

“Woods and Doherty weren’t part of the detail, nor were they personally responsible for the ambassador’s security, but they stepped into the breach when the attacks occurred and their actions saved others lives -- and they shouldn’t be lumped in with the security detail,” one senior official said, speaking only on condition of anonymity because he wasn’t authorized to speak publicly about the State Department.

The administration has not fully described the two former Navy SEALs' activities, characterizing their work only vaguely as being security related. “Our embassies could not carry on our critical work around the world without the service and sacrifice of brave people like Tyrone and Glen," Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said after the attacks.

As recently as Sunday, UN Ambassador Susan Rice gave a similar description. “Two of the four Americans who were killed were there providing security. That was their function. And indeed, there were many other colleagues who were doing the same with them,” Rice told ABC's This Week program.

In fact, officials said, the two men were personal service contractors whose official function was described as "embassy security," but whose work did not involve personal protection of the ambassador or perimeter security of the compound.

The details emerged the same day that U.S. officials confirmed in public a Washington Guardian story Friday that U.S. intelligence believes al-Qaida or its affiliates played a role in the attack. "We are looking at indications that individuals involved in the attack may have had connections to Al Qaeda or Al Qaeda's affiliates," Matt Olsen, the director of the National Counterrorism Center, told lawmakers.

Administration officials had downplayed al-Qaida connections shortly after the attack.

Many U.S. agencies in foreign hotspots like Benghazi rely on and even share contract workers with special skills like those of retired Navy SEALs for security, reconnaissance and threat assessments.

Unlike full embassies such as the one in Tripoli, consulates like Benghazi usually don’t have a contingent of Marines to provide security, and private contractors help fulfill some of those responsibilities. The Washington Guardian reported last week concerns about the embassy security that predated the deadly attack.

Those briefed on the latest intelligence say investigators are trying to determine when and why Stevens’ official State Department security team got separated from the ambassador when the attacks occurred the evening of Sept. 11.

The separation of the team from the ambassador remains one of the more serious matters under review, the officials said.

In addition, while the administration has downplayed any link to al-Qaida, there is evidence some of the attackers were affiliated with another group that sympathizes with al-Qaida and has grown more influential in Libya and other parts of north Africa.

State Department officials did not respond to emails or phone calls seeking comment Wednesday.

The current evidence leads U.S. intelligence to believe that a band of Islamist extremists with some ties to the north African affiliate of al-Qaida had accumulated a stash of weapons and extra human muscle, performed some reconnaissance to identify possible U.S. targets, and may have even infiltrated the Libyan security forces that help protect the consulate in hopes of eventually conducting a terrorist operation somewhere in Benghazi.

However, U.S. intelligence does not believe -- at present -- that the attackers specifically targeted Stevens, official said. Instead, they think the attackers sprang into action when, seeing crowds forming outside the consulate on Sept. 11, they perceived an opportunity to carry out a terrorist attack, officials said.

“Yes, they were killed in a terrorist attack on our embassy,” Olsen told the Senate Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee on Wednesday. “The best information we have now, the facts that we have now, indicates an opportunistic attack on our embassy.”

U.S. officials say they have some evidence at least one of the attackers had prior connections to al-Qaida's senior leadership and that others were linked to a sympathetic spinoff group in northern Africa known as al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, which is gaining influence in Libya.

Specifically, U.S. intelligence is investigating whether there is any connection to an al-Qaida-linked player named Sufyan Ben Qumu, who was captured by U.S. officials after the September 11, 2001 attacks and held at Guantanamo Bay for years before being released to Libyan authorities by the Bush administration in 2007. Qumu has emerged in recent months as an increasingly influential Islamist figure in eastern Libya, near Benghazi.

Fox News reported Wednesday night he might be a mastermind of the attack, but U.S. intelligence officials said such conclusions are premature.

“There’s an active effort to uncover those individuals and groups who were responsible for the attack. Any suggestion that a leading suspect or ‘mastermind’ of the attack has been identified at this point is premature. It is safe to assume that any significant extremist in Eastern Libya is going to be under a lot of scrutiny right now," one U.S. intelligence official told the Washington Guardian.

U.S. intelligence believes part of the motivation for launching the attack was a video from al-Qaida leader Ayman al-Zawahiri that surfaced the night of Sept. 10, imploring Libyans to attack Americans in retribution for the U.S. drone strike that killed Libyan-born al-Qaida leader Abu Yahya al-Libi in June.

The Washington Guardian reported on Friday that U.S. intelligence had intercepted and translated Zawahiri’s message imploring Libyans to attack U.S. officials the night before the consulate attack and were still analyzing its significance when the ambassador was killed. No significant changes to security countermeasures at the diplomatic mission were taken until after the compound was overrun.

The White House claims two ex-SEALs killed in Libya were inept security guards. The truth? They volunteered for duty and died heroes. But that doesn't serve an Obama political purpose, now does it?

According to the Obama administration's United Nations ambassador, Susan Rice, the two former Navy SEALs who died defending the Benghazi consulate from attack this month, Tyrone Woods, 41, and Glen Doherty, 42, were State Department employees on the consulate's security detail when they somehow got overpowered by a mob that was enraged by an anti-Islamic film.

That's questionable, given that the consulate endured a sustained paramilitary-style attack that left the consulate aflame, killed U.S. ambassador Chris Stevens and diplomat Sean Smith, and ended with a desperate trail of bloody handprints across the consulate walls.

"Tragically, two of the four Americans who were killed were there providing security. That was their function," Rice told ABC News' Jake Tapper in an interview earlier this week.

Hold on. It now comes to light that they weren't State Department employees and they weren't there to protect the consulate. They bravely did it on their own.

In reality, they were two contractors working on a separate mission — with at least one tracking down missing shoulder-fired missiles, according to ABC News.

"Woods and Doherty weren't part of the detail, nor were they personally responsible for the ambassador's security, but they stepped into the breach when the attacks occurred and their actions saved the lives of others," an unnamed U.S. official told the Washington Guardian.

So as the consulate was pummeled with mortar fire from an organized al-Qaida terrorist attack, the two men, with no preparation and no ground intelligence, just plain stepped forward without any obligation to do so, and died defending the U.S. after the non-U.S. contractors who were paid to do that ran away.

But the White House makes no such recognition.

That's because the two men's selfless act raises questions about how serious Secretary of State Hillary Clinton's State Department was about defending U.S. outposts from potential al-Qaida terror attacks.

Already a damning picture is building, given that the U.S. knew about an al-Qaida revenge threat following the killing of a Libyan terrorist in Pakistan, the Libyan government says it gave a three-day warning of an attack, Stevens himself expressed concern about being on an al-Qaida hit list, and Smith wrote in a computer bulletin board posting the chilling words "if we don't get killed tonight."

But if that picture of malfeasance doesn't fit the "narrative" of the Obama administration, then the sacrifice of the ex-SEALs gets covered up and they go out to history as bumblers.

It just goes to show the willingness of the Obama administration to politicize the patriotic missions of the SEALs to its own shameless ends.

The Obama administration has always sought to politicize the SEALs — from President Obama trying to make political hay out of the SEAL raid on bin Laden to win re-election, to his recent attempt to motivate his campaign staff in Las Vegas by comparing their electioneering to the ultimate sacrifice of the two former SEALs.

Now the Obama team is concealing what the two former SEALs really did and spinning their act as just that of helpless security guards.

Frankly, the SEALs deserve better.

Is there ever going to come a time when the patriotism of the SEALs is left out of politics? Not so long as Obama is president. To our president, patriotism is partisanship and partisanship is patriotism.

Read More At IBD: http://news.investors.com/ibd-editorials/092012-626505-white-house-uses-the-seals-for-political-cover.htm#ixzz27xjQWT00

Benghazi-Gate: A Timeline of Government Deceit, Deception, and Outright Lies

Bombshell: Obama Administration Deleted State Dept. Memo From Internet After Discovering Al-Qaeda Was Behind Benghazi Attack

Posted by Jim Hoft on Thursday, September 27, 2012, 9:17 AM

So what was their first action?

Did they secure the compound? – No, that took over a week to get FBI agents to the consulate

Did they acknowledge it was an Al-Qaeda attack? No, Obama this week blamed the terror attack on a YouTube protest.

Here’s what they did – They scrubbed a damning State Department memo from the internet–

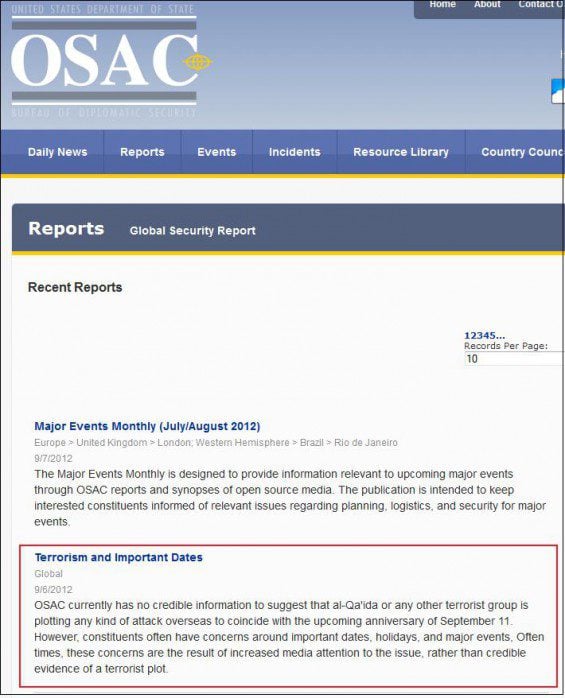

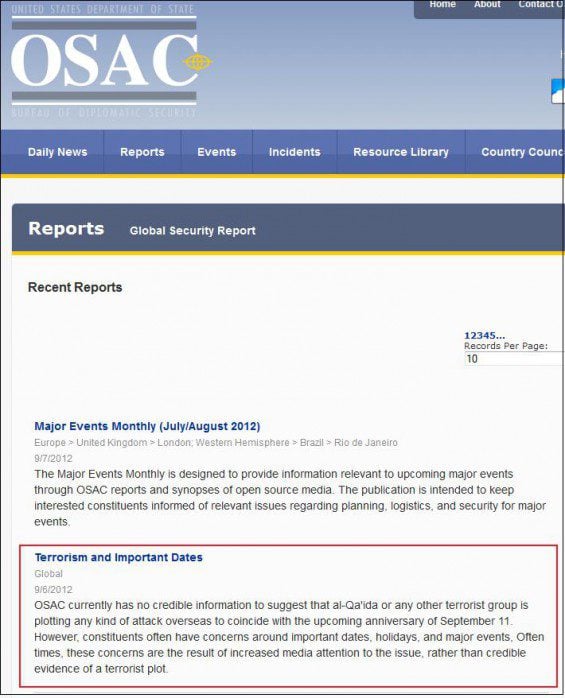

On Wednesday September 12, 2012 blogger Speak With Authority discovered that five days before 9-11, the US State Department sent out a memo announcing no credible security threats against the United States on the anniversary of 9-11.

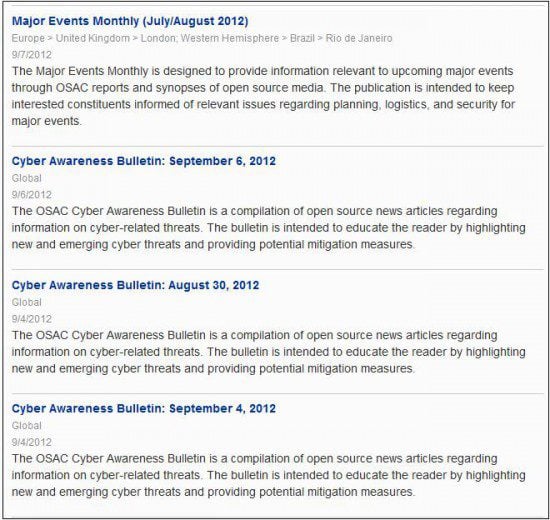

The Overseas Security Advisory Council, who posted the memo, is part of the Bureau of Diplomatic Security under the U.S. Department of State.

Here is a screengrab of the memo at the OSAC website:

The OSAC memo said:

The State Department scrubbed the letter from its OSAC website.

The damning memo is gone.

How convenient. They flushed the damning memo down the internet memory hole.

Blue Mountain

Did they secure the compound? – No, that took over a week to get FBI agents to the consulate

Did they acknowledge it was an Al-Qaeda attack? No, Obama this week blamed the terror attack on a YouTube protest.

Here’s what they did – They scrubbed a damning State Department memo from the internet–

On Wednesday September 12, 2012 blogger Speak With Authority discovered that five days before 9-11, the US State Department sent out a memo announcing no credible security threats against the United States on the anniversary of 9-11.

The Overseas Security Advisory Council, who posted the memo, is part of the Bureau of Diplomatic Security under the U.S. Department of State.

Here is a screengrab of the memo at the OSAC website:

The OSAC memo said:

Terrorism and Important DatesBut now it’s gone.

Global

9/6/2012

OSAC currently has no credible information to suggest that al-Qa’ida or any other terrorist group is plotting any kind of attack overseas to coincide with the upcoming anniversary of September 11. However, constituents often have concerns around important dates, holidays, and major events, Often times, these concerns are the result of increased media attention to the issue, rather than credible evidence of a terrorist plot.

The State Department scrubbed the letter from its OSAC website.

The damning memo is gone.

How convenient. They flushed the damning memo down the internet memory hole.

Blue Mountain

OUR RECENT TASKS

We’d like to give you an insight into some of the tasks we have undertaken recently, so you can appreciate the variety of work we are able to undertake:

close protection for a high net worth businessman in London; protection of media teams operating in Yemen and Libya; gathering of evidence for

commercial fraud; assessment of security at numerous facilities in Libya; provision and training of static guard teams for high profile resorts and hotels;

close protection and security guard forces for embassies; and security training teams for high risk environments. Of course, there is much more we would

like to tell you about…..August 2012

We’d like to give you an insight into some of the tasks we have undertaken recently, so you can appreciate the variety of work we are able to undertake:

close protection for a high net worth businessman in London; protection of media teams operating in Yemen and Libya; gathering of evidence for

commercial fraud; assessment of security at numerous facilities in Libya; provision and training of static guard teams for high profile resorts and hotels;

close protection and security guard forces for embassies; and security training teams for high risk environments. Of course, there is much more we would

like to tell you about…..August 2012

"Al-Qaeda is on the path to defeat." -- President Barack Obama: Sept 6th, 2012, at the Democratic Convention.

Late yesterday afternoon, in an obvious attempt to rescue President Obama from what could and should be a brutal round of Sunday shows examining the cover up the White House is currently engaged in with respect to the sacking of our consulate in Libya, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) released a statement revising its assessment of the attack. It is now the official position of the American intelligence community that what happened in Benghazi was a pre-planned terrorist attack.

The statement comes from Shawn Turner, director of public affairs for National Intelligence -- the office that speaks for the intelligence community as a whole:As we learned more about the attack, we revised our initial assessment to reflect new information indicating that it was a deliberate and organized terrorist attack carried out by extremists. It remains unclear if any group or person exercised overall command and control of the attack, and if extremist group leaders directed their members to participate.

This is not news. In the last few days, the White House and State Department have both made statements saying exactly that.

This, however, is news and should be read carefully:

In the immediate aftermath, there was information that led us to assess that the attack began spontaneously following protests earlier that day at our embassy in Cairo. We provided that initial assessment to Executive Branch officials and members of Congress, who used that information to discuss the attack publicly and provide updates as they became available. Throughout our investigation we continued to emphasize that information gathered was preliminary and evolving.

There's no question that what we have here is the DNI (Obama appointee James Clapper) attempting to fall on his sword and to put an end to the drumbeat of scandal coming mostly from Republicans and right-of-center media. What's been exposed, just weeks before a presidential election, is the fact that in the aftermath of the Benghazi attack, the White House and State Department knowingly misled and lied to the American people about what they knew and when they knew it.

But what the DNI statement is really meant to do is muddy the waters.

The statement deliberately omits any information as to exactly when the determination was made that Benghazi was indeed a terrorist attack. Most importantly, nothing in the statement contradicts numerous news reports that U.S. officials were certain within 24 hours that they were dealing with a terrorist attack and not a spontaneous protest gone bad.

In other words, the DNI statement is so intentionally vague that it could read as confirmation that our government knew within 24 hours that Benghazi was a terrorist attack and still lied about it for days afterward.

And this, my friends, is how a cover up works.

And so, the only response to this cynical muddying of the waters is a 30,000 foot approach that might help connect some dots.

Standing on the shoulders of those who have done the admirable work of digging into and investigating this story (most notably, Brett Baier of Fox News, Stephen Hayes of the Weekly Standard, Jake Tapper of ABC News, and the Daily Beast's Eli Lake), what I want to do is lay out a timeline of known facts that answer a very simple question:

What did our government know and what were we told when they knew it?

What you'll see below was inspired by the vitally important video-report Brett Baier closed "Special Report" with last night, but this will hopefully go into even greater detail. We'll also look into three specific areas: 1) Security failures. 2) The lies. 3) The attempted cover up of numbers one and two.

---

SECURITY FAILURES

In an attempt to justify that the security at our Libyan consulate in Benghazi was "adequate," the White House laid a narrative along two tracks. The first, obviously, was that there was no way anyone could've predicted that a "spontaneous" protest would go bad. In fact, that defense would be the White House position for a full eight days, until Sept 20th, when White House Spokesman Jay Carney would finally admit it was "self-evident" Benghazi was a terror attack. The second narrative track, however, is as shaky as the first. Essentially, the Administration's line is that, based on what we knew, security was adequate.

That's a judgment call, I guess, but let's look at what we did know for a fact prior to the sacking of the consulate and determine if having no Marines, no bullet-proof windows, no threat assessment, and no real security other than locks on the doors was indeed adequate…

1. We'll start with what is the most underreported fact of this entire episode: the fact that this very same consulate had been targeted and attacked just a few months earlier, on June 6, in retaliation for a drone strike on a top al-Qaeda operative:

U.S. mission in Benghazi attacked to avenge al Qaeda

The United States diplomatic office in the Libyan city of Benghazi was attacked Tuesday night, the embassy in the capital Tripoli said Wednesday.

A Libyan security source told CNN a jihadist group that is suspected of carrying out the strike, the Imprisoned Omar Abdul Rahman Brigades, left leaflets at the scene claiming the attack was in retaliation for the death of Libyan al Qaeda No. 2 Abu Yahya al Libi.

"Fortunately, no one was injured" in the improvised explosive device attack, the embassy said.

2. It was the eleventh anniversary of 9/11, a date that should mean heightened security regardless of what our intelligence says.

3. In the days just prior to the Benghazi attack (September 9 and 10), al-Qaeda chief Ayman al-Zawahri….

….posted a 42-minute video on Jihadist forums urging Libyans to attack Americans to avenge the death of Abu Yahya al-Libi, the terror organization’s second-in-command, whom U.S. drones killed in June of 2012 in Pakistan.

In the video, al-Zawahri said al-Libi’s “blood is calling, urging and inciting you to fight and kill the Crusaders,” leading up to a date heralded and celebrated by radical Islamists.

Another version of the video was actually posted on YouTube on September 9[.]

4. Just a couple of months prior to the Benghazi attack….

…an unclassified report published in August that fingers Qumu as a key al Qaeda operative in Libya. The report (“Al Qaeda in Libya: A Profile”) was prepared by the research division of the Library of Congress (LOC) under an agreement with the Defense Department’s Combating Terrorism Technical Support Office.

The report details al Qaeda’s plans for Libya, including the growth of a clandestine terrorist network that has attempted to hide its presence. The U.S military has concluded that al Qaeda is in the final phase of a three-step process for developing a full-blown al Qaeda affiliate.

5. Our assassinated Ambassador, Christopher Stevens, feared al-Qaeda's growing influence in Libya and believed he was on a hit list.

6. Sean Smith, one of our diplomats killed along with Stevens, also feared for his life prior to the attack:

One of the American diplomats killed Tuesday in a bloody attack on a Libyan Consulate told pals in an online gaming forum hours earlier that he'd seen suspicious people taking pictures outside his compound and wondered if he and his team might "die tonight." …

But hours before the bloody assault, Smith sent a message to Alex Gianturco, the director of "Goonswarm," Smith's online gaming team or "guild."

“Assuming we don’t die tonight,” the message, which was first reported by Wired, read. “We saw one of our ‘police’ that guard the compound taking pictures.”

Within hours of posting that message, Smith, a husband and father of two, was dead. Gianturco, who could not be reached for further comment, got the word out to fellow gamers, according to Wired.

What we have here are six concrete, non-speculative red flags that indicated our consulate and Ambassador were in danger, vulnerable to attack, and targets.

To justify a lack of adequate security, the Obama administration spent a week blaming the attack on a "spontaneous" demonstration they couldn’t have possibly predicted would occur. We now know that's simply not true. But here are two more justifications we were told:

1. CNN Sept 21: Clinton says Stevens was not worried about being hit by al-qaeda:

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said Thursday she has "absolutely no information or reason to believe there is any basis" to suggest that U.S. Ambassador to Libya Chris Stevens believed he was on an al Qaeda hit list.

The remark came after a source familiar with Stevens' thinking told CNN that in the months leading up to his death, Stevens worried about constant security threats in Benghazi and mentioned that his name was on an al Qaeda hit list.

So Clinton is saying that Stevens wasn't on a al-Qaeda hit list. Stevens' diary says he was. Oh. Okay.

2. White House Spokesman Jay Carney on Sept 14: [emphasis added]

ABC NEWS' JAKE TAPPER: One of my colleagues in the Associated Press asked you a direct question, was there any direct intelligence suggesting that there would be an attack on the U.S. consulates. You said that a story — referred to a story being false and said there was no actionable intelligence, but you didn’t answer his question. Was there any intelligence, period — intelligence, period, suggesting that there was going to be an attack on either the –

CARNEY: There was no intelligence that in any way could have been acted on to prevent these attacks. It is — I mean, I think the DNI spokesman was very declarative about this, that the report is false. The report suggested that there was intelligence that was available prior to this that led us to believe that this facility would be attacked, and that is false.

Note Carney's careful wording; how determined he is to stay in the arena of "actionable" intelligence and intelligence that "could have been acted on to prevent these attacks." Also note how Carney never answers Tapper's general question about "any intelligence" or intelligence in general.

Summation: Let's give our government the benefit of the doubt and assume the stories about Stevens' fear of being an al-Qaeda target are incorrect -- or, if true, that for some inexplicable reason he never communicated those fears to his superiors. Here's what is indisputable…

The Obama administration didn’t act upon the fact that the anniversary of 9/11 is an obvious date to be wary of or the fact that our consulate had already been targeted and attacked just a few months prior. We also didn’t act upon a report that said al-Qaeda's influence was growing in Libya or a video-threat released by an al-Qaeda chief just days prior to the red-flag date of 9/11.

But security was adequate.

WHAT DID OUR GOVERNMENT KNOW AND WHEN DID THEY KNOW IT?

Taking the just-released DNI statement at its word, let's argue that for a time our intelligence services believed the fatal Benghazi attack was a "spontaneous" protest gone bad. Then, on a date not specified in the DNI statement, the assessment was updated to a pre-meditated terrorist attack committed by affiliates of al-Qaeda. None of that contradicts what we already knew.

According to a number of reports based on numerous sources, we can ascertain exactly when our government determined Benghazi was a terrorist attack -- and that was just 24 hours after the attack.

Let's run through the facts:

1. In a Rose Garden statement the morning after the attack, the President himself referred to the attacks as terror:

No acts of terror will ever shake the resolve of this great nation, alter that character, or eclipse the light of the values that we stand for. Today we mourn four more Americans who represent the very best of the United States of America. We will not waver in our commitment to see that justice is done for this terrible act. And make no mistake, justice will be done.

2. "Intelligence sources said that the Obama administration internally labeled the attack terrorism from the first day…"

… in order to unlock and mobilize certain resources to respond, and that officials were looking for one specific suspect. The sources said the intelligence community knew by Sept. 12 that the militant Ansar al-Shariah and Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb were likely behind the strike.

3. "In the hours following the 9/11 anniversary attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya…"

…U.S. intelligence agencies monitored communications from jihadists affiliated with the group that led the attack and members of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), the group’s North African affiliate.

In the communications, members of Ansar al-Sharia (AAS) bragged about their successful attack against the American consulate and the U.S. ambassador, according to three U.S. intelligence officials who spoke to The Daily Beast anonymously because they were not authorized to talk to the press.

4. "Within 24 hours of the 9-11 anniversary attack on the United States consulate in Benghazi…"

U.S. intelligence agencies had strong indications al Qaeda–affiliated operatives were behind the attack, and had even pinpointed the location of one of those attackers. Three separate U.S. intelligence officials who spoke to The Daily Beast said the early information was enough to show that the attack was planned and the work of al Qaeda affiliates operating in Eastern Libya.

Again, let's be clear: The DNI statement released yesterday does not dispute any of this. And yet….

THE NARRATIVE: OUR GOVERNMENT TOLD US THAT WASN'T TRUE

For an extensive rundown of the false and misleading statements surrounding the Benghazi attack, let me refer you again to Brett Baier's video report and to a Washington Post rundown put together by Glenn Kessler.

What I want to focus on here is the administration's narrative. There's simply no longer any question that in the days following the attack, a coordinated White House narrative was orchestrated that was intentionally misleading and completely false.

And that narrative went something like this:

1. There was no security failure at the consulate. The attack was birthed by a spontaneous protest gone bad -- so how could we have known?

2. Obama's brag before the country that al-Qaeda was on the road to defeat just five days before the Benghazi attack remains true. After all, this wasn't a terrorist attack, it was a protest gone bad.

3. Obama's Middle East policy of disengagement and assuming his own awesomeness would buy us goodwill with radicals worked. After all, these massive, deadly protests in two dozen countries have nothing to do with anti-American sentiment; the bad guy is a Coptic Christian filmmaker who insulted Muhammad.

I'll reiterate that this is how a cover up works. You don’t tell the truth and you don't lie; what you do is manufacture a false narrative built on misleading statements that aren’t outright lies. As you can see, many of the statements made by President Obama, Secretary of State Clinton, Jay Carney, and U.N. Ambassador Susan Rice are loaded with caveats and escape hatches: "Based on what we know…" and "What we do know is…"

Defenders of the President and his administration officials will and are using these escape hatches to defend the intentional spinning of a patently false narrative. But there's absolutely no question that for a full week this false narrative -- a glaring lie of omission -- was also used to strike down, downplay, dismiss, and distract from any raising of the question that what might've happened in Benghazi was the work of terrorists.

Moreover, this narrative was so intentionally stifling and oppressive, it wouldn’t even allow room for an either/or possibility. The lie of omission was that no administration official told us that what happened "could've been" or "might've been" a terrorist attack. Quite the opposite. The narrative was used to tell us the raising of that possibility was outrageous.

This, even in the face of numerous news outlets reporting just a day or two after the attack that terrorism was a likely motive. On September 12, both Fox News and CBS News reported the possibility, and on September 13, CNN joined in.

And yet, this narrative lie of omission that was used to scape-goat this filmmaker and to shout down anyone who even entertained the notion of terrorism, remained firmly in place until Sept. 20, the day Jay Carney finally admitted it was "self-evident" terrorism was behind the attack.

But just day before, on Sept 19, the White House was using this narrative to treat those who even raised the possibility of a terror attack like they were crazy. Watch this bizarre exchange between Carney and CBS News White House correspondent Bill Plante a full eight days after the attack:

-

-

That memorable exchange occurred the very same day National Counterterrorism Center Director Matthew Olsen told Congress that the Benghazi attack was indeed an act of terror.

THE LIES

Not every statement made by an administration official contained the necessary escape hatches to avoid being outright lies. In fact, if you look closely at numerous statements made by Susan Rice and Jay Carney, regardless of how much benefit of the doubt Obama's defenders wish to summon -- both of them looked the American people in the eye and lied. Let's start with Carney.

The following is a transcript of a Sept. 14 exchange between Carney and ABC's Jake Tapper: [emphasis added]

TAPPER: Wouldn’t it seem logical that the anniversary of 9/11 would be a time that you would want to have extra security around diplomats and military posts?

CARNEY: Well, as you know, there — we are very vigilant around anniversaries like 9/11. The president is always briefed and brought up to speed on all the precautions being taken. But let’s be -

TAPPER: Obviously not vigilant enough.

CARNEY: Jake, let’s be clear. This — these protests were in reaction to a video that had spread to the region [1]–

TAPPER: At Benghazi?

CARNEY: We certainly don’t know; we don’t know otherwise. You know, we have no information to suggest that it was a preplanned attack. [2] The unrest we’ve seen around the region has been in reaction to a video that Muslims, many Muslims find offensive. And while the violence is reprehensible and unjustified, it is not a reaction to the 9/11 anniversary that we know of or to U.S. policy.

TAPPER: The group around the Benghazi post was well-armed, it was a well-coordinated attack. Do you think it was a spontaneous protest against a movie?

CARNEY: Look, this is obviously under investigation, and I don’t have — but I answered the question.

ANOTHER REPORTER: But your operating assumptions — your operating assumption is that that was — that was in response to the video, in Benghazi? I just want to clear that up. That’s the framework; that’s the operating assumption?

CARNEY: It’s not an assumption –

TAPPER: Administration officials have said that it looks like this was something other than -

CARNEY: I think there have been misreports on this, Jake, even in the press, which some of it has been speculative. What I’m telling you is this is under investigation. The unrest around the region has been in response to this video. We do not, at this moment, have information to suggest or to tell you that would indicate that any of this unrest was preplanned. [3]

What I've bolded and numbered are undeniably false statements. On Sept. 14, a full two days after the attack, Carney is falsely but declaratively stating as fact that…

1. "[L]et’s be clear. This — these protests were in reaction to a video that had spread to the region."

Carney isn't stating this as a possibility, he is stating it as settled fact. Even if you give the White House as much benefit of the doubt as possible, no one believed that was settled fact. And yet, this is what the White House told America.

2. "[W]e have no information to suggest that it was a preplanned attack."

That's just false. By this time that was probably the only information the White House had.

3. Carney doubles down on the patently false "no information" claim.

As we now know, numerous reports based on numerous sources say that within 24 hours of the sacking of our consulate, we not only had information that al-Qaeda was behind it, but on day one, in order to release the necessary resources, we had designated it as a terror attack.

If that isn't bad enough, a full five days later, on Sept. 19, Carney had this exchange with CBS News White House correspondent Bill Plante: [emphasis added]

PLANTE: You are still maintaining that there was no evidence of a pre-planned attack--

CARNEY: Bill, let me just repeat now--

PLANTE: But how is it that the attackers had RPGs, automatic weapons, mortars…

CARNEY: Bill, I know you've done a little bit of reading about Libya since the unrest that began with Gaddafi. The place has an abundance of weapons.

PLANTE: But you expect a street mob to come armed that way?

CARNEY: There are unfortunately many bad actors throughout the region and they're very armed. ….

PLANTE: But they planned to do it, don't you think?

CARNEY: They might, or they might not. All I can tell you is that based on the information that we had then and have now we do not yet have indication that it was pre-planned or pre-meditated. There's an active investigation. If that active investigation produces facts that lead to a different conclusion, we will make clear that that is where the investigation has led. Our interest is in finding out the facts of what happened, not taking what we've read in the newspaper and making bold assertions that we know what happened.

Once again, you have Carney stating declaratively and falsely stating that "we [still] do not yet have indication" that the Benghazi attack was pre-planned -- eight days after the attack!

Again, under the most generous benefit of the doubt one can summon, what you have in these two examples is the White House lying to the media and to the American people.

Impossibly enough, what Susan Rice did was even worse.

On September 16, a full four days after the attack, and at least three days after the White House knew Benghazi had been a terror attack, Rice was sent out on a round-robin of five Sunday morning news shows to push a narrative the White House knew was false.

What's worse, however, is that like Carney, Rice also made declaratively false statements: [emphasis added]

Fox News Sunday:

RICE: The best information and the best assessment we have today is that was, in fact, not a pre-planned and pre-meditated attack. That what happened initially -- it was a spontaneous reaction to what had just transpired in Cairo, as a consequence of the video, that people gathered outside the embassy and then it grew very violent. Those with extremist ties joined the fray and came with heavy weapons, which unfortunately are quite common in post-revolutionary Libya. And that then spun out of control. We don't see at this point -- signs that this was a coordinated, pre-meditated attack. Obviously we'll wait for the results of the investigation and we don't want to jump to conclusions before then. But I do think it's important for the American people to know our best current assessment.

Face the Nation:

As soon as the president of Libya's National Congress, Mohamed Magariaf, finished telling host Bob Scieffer….

The way these perpetrators acted and moved, I think we-- and they're choosing the specific date for this so-called demonstration, I think we have no-- this leaves us with no doubt that this has preplanned, determined-- predetermined. months ago, and they were planning this criminal act since their-- since their arrival.

…Ambassador Rice took her turn:

BOB SCHIEFFER: But you do not agree with [Magariaf] that this was something that had been plotted out several months ago?

SUSAN RICE: We do not-- we do not have information at present that leads us to conclude that this was premeditated or preplanned.

This Week:

JAKE TAPPER: It just seems that the U.S. government is powerless as this -- as this maelstrom erupts.

RICE: It's actually the opposite. First of all, let's be clear about what transpired here. What happened this week in Cairo, in Benghazi, in many other parts of the region...

TAPPER: Tunisia, Khartoum...

RICE: ... was a result -- a direct result of a heinous and offensive video that was widely disseminated, that the U.S. government had nothing to do with, which we have made clear is reprehensible and disgusting. We have also been very clear in saying that there is no excuse for violence, there is -- that we have condemned it in the strongest possible terms.

Rice declaratively states as settled fact that the Benghazi attack was a "direct result" of the video.

Meet the Press:

DAVID GREGORY: Was there a failure here that this administration is responsible for, whether it’s an intelligence failure, a failure to see this coming, or a failure to adequately protect U.S. embassies and installations from a spontaneous kind of reaction like this?

SUSAN RICE: David, I don’t think so. First of all we had no actionable intelligence to suggest that-- that any attack on our facility in Benghazi was imminent. In Cairo, we did have indications that there was the risk that the video might spark some-- some protests and our embassy, in fact, acted accordingly, and had called upon the Egyptian authorities to-- to reinforce our facility. What we have seen as-- with respect to the security response, obviously we had security personnel in Benghazi, a-- a significant number, and tragically, among those four that were killed were two of our security personnel. But what happened, obviously, overwhelmed the security we had in place which is why the president ordered additional reinforcements to Tripoli and-- and why elsewhere in the world we have been working with governments to ensure they take up their obligations to protect us and we reinforce where necessary.

Note how, like Carney earlier, Rice rephrases the question into "actionable" intelligence. Because we most certainly had intelligence, including a video threat from a top al-Qaeda operative.

ONE MORE DECEIT

As if all of the above isn’t on its own frustrating, heart-breaking, maddening, and unforgivable enough, let me close with one more deceit.

During her Sunday blitz, and in an attempt to explain the criminal and fatal lack of security in Benghazi, Susan Rice told Chris Wallace this:

WALLACE: And the last question: Terror cells in Benghazi had carried out five attacks since April, including one at this same consulate-- a bombing at this same consulate in June. Should U.S. security been tighter at that consulate given the history of terror activity in Benghazi?

RICE: We obviously did have a strong security presence and unfortunately, two of the four Americans who died in Benghazi were there to provide security. But that obviously wasn’t sufficient in the circumstances to prevent the overrun of the consulate. This is among the things that will obviously be looked at as the investigation as the investigation unfolds.

That's also not true.

Whatever security there was, the White House cannot use two dead Navy SEALs as window dressing that makes some sort of case that says, Well, at least the White House had Navy SEALs protecting the ambassador and the consulate -- because regardless of the spin Rice put on it, that simply wasn't the case:

As recently as Sunday, UN Ambassador Susan Rice gave a similar description. “Two of the four Americans who were killed were there providing security. That was their function. And indeed, there were many other colleagues who were doing the same with them,” Rice told ABC's This Week program.

In fact, officials said, the two men were personal service contractors whose official function was described as "embassy security," but whose work did not involve personal protection of the ambassador or perimeter security of the compound. …

They stepped into action, however, when Stevens became separated from the small security detail normally assigned to protect him when he traveled from the more fortified embassy in Tripoli to Benghazi, the officials said.

The two ex-Seals and others engaged in a lengthy firefight with the extremists who attacked the compound, a fight that stretched from the inner area of the consulate to an outside annex and a nearby safe house -- a location that the insurgents appeared to know about, the officials said.

The Weekly Standard's Stephen Hayes asks:

Some of the misleading information provided to the public could not possibly have been a result of incomplete or evolving intelligence. The information about security for the ambassador and the compound, for instance, would have been readily available to administration officials from the beginning. And yet when Susan Rice appeared on five political talk shows on September 16, she erroneously claimed that the two ex-Navy SEALs killed in the attack were, along with several colleagues, providing security. They were not. Why did she say this?

Good question. But I have a better one: Why did our president say the same:Glen and Tyrone had each served America as Navy SEALs for many years, before continuing their service providing security for our diplomats in Libya. They died as they lived their lives — defending their fellow Americans, and advancing the values that all of us hold dear.

This is a legitimate scandal of the highest order. Four Americans are dead, our government is still attempting to cover up what really happened, and as of this writing. the F.B.I still hasn't gained access to the consulate.

And what's the response of those charged with the sacred duty of holding our government accountable?

Breaking: Fox News confirms Obama admin designated Benghazi sacking a terror attack within first 24 hours

September 27, 2012 by Ed Morrissey

U.S. intelligence officials knew within 24 hours of the assault on the U.S. Consulate in Libya that it was a terrorist attack and suspected Al Qaeda-tied elements were involved, sources told Fox News — though it took the administration a week to acknowledge it.Four days later, the White House sent UN Ambassador Susan Rice to five different Sunday talk shows to claim that the sacking and assassination sprang from a “spontaneous” demonstration. That no longer can be explained as initial confusion over conflicting reports; it is now clearly a lie told by the White House. Jennifer Rubin pointed this out at the Washington Post even before the Fox report, and wondered where the national media that screeched at every claim by George W. Bush has suddenly become so comfortable with an administration that flat-out lies to them:

The account conflicts with claims on the Sunday after the attack by U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Susan Rice that the administration believed the strike was a “spontaneous” event triggered by protests in Egypt over an anti-Islam film.

Two senior U.S. officials said the Obama administration internally labeled the attack terrorism from the first day in order to unlock and mobilize certain resources to respond, and that officials were looking for one specific suspect.

Eli Lake let loose a bombshell yesterday: “Within 24 hours of the 9-11 anniversary attack on the United States consulate in Benghazi, U.S. intelligence agencies had strong indications al Qaeda–affiliated operatives were behind the attack, and had even pinpointed the location of one of those attackers. Three separate U.S. intelligence officials who spoke to The Daily Beast said the early information was enough to show that the attack was planned and the work of al Qaeda affiliates operating in Eastern Libya.”Jennifer should start by asking her own colleagues at the Post. Aside from Glenn Kessler, who began pointing out the politics involved in the cover story today, the newspaper hasn’t done much to challenge Rice’s account or the fallout from its collapse.

Obviously the report, if true, suggests that the White House lied to the American people by insisting for over a week that this was a spontaneous attack. It is one thing for the president to be so benighted as to think a video sets off multiple attacks on Sept. 11. It is quite another to send out his advisers, including his own spokesman, to mislead voters. …

And finally, now is the time when we see if reporters and pundits are more than shills for the president. The incompetency, and perhaps mendacity, of thee White House here is severe. The media’s glaring unwillingness to hold the president accountable for his actions can be at least partially remedied if they pursue the story vigorously. Even though Bush in good faith believed his intelligence community’s take on weapons of mass destruction, the left-leaning elites hollered, “Bush lied, people died!” But here we have dead Americans and an cover story in shreds. Why is there not, at a bare minimum, a call for answers? Isn’t this a top-of-the-fold issue? Well, my guess is that pundits and reporters alike in the mainstream media will do their best to soften and downplay the story.

I hope I’m wrong and that the media live up to their journalistic responsibilities, but I see little evidence that an epidemic of fairness is breaking out in the mainstream media. All the more reason, then, for lawmakers and Romney to push for answers. Certainly, we shouldn’t have a president in office who would lie to the American people about a critical national security issue for the sake of his own reelection, right?

Update: Jim DeMint called for a complete investigation into the White House’s “misleading” statements even before Fox broke this news:

Officials claimed the attacks were “spontaneous” and a result of a protest that had “spun out of control.” Ambassador Rice denied it was premeditated, stating that the protest was “hijacked by some individual clusters of extremists…and then it evolved from there.”It’s time to flush out the liars.

Then, finally, the National Counterterrosim Center Director Matthew Olsen stated in a Senate hearing the four Americans were killed “in the course of a terror attack” that may have connections to al Qaeda, but that we do not have specific intelligence of “significant advance planning”.

Again, this is a different narrative described by Libyan President Megariaf, who said the attack was carried out by foreign militants who had infiltrated Libya and had been planning these events for months. The contradictory and changing stories stemming from the same events are worrisome.

It’s far past time to get all the facts. We need a comprehensive detailed report rather than waiting for various officials to dribble them out one interview at a time.

Senator Bob Corker (R-Tenn.) and I have introduced legislation to require the Obama Administration to conduct an official investigation and issue a report on the September 11-13, 2012 attacks on United States missions in Libya, Egypt, and Yemen within 30 days. It also requires the Secretary of State to submit recommended changes to security procedures.

left-leaning Center for American Progress.

by Joel B. Pollak

Former Navy SEALs are speaking out after President Barack Obama referred to recent events in the Middle East, including the deaths of two former Navy SEALs, as "bumps in the road."

Tyrone S. Woods and Glen A. Doherty were providing security at the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya when it was attacked on 9/11. They were both hailed in the aftermath of the attacks by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. Both had gone into private security after retiring from the Navy after distinguished careers.

Former SEAL and current Montana State Senator Ryan Zinke issued the following statement:

Former Navy SEALs to Obama: 'We Are Not Bumps in the Road'

The President refuses to admit that his policy of appeasement and apology has failed. The murder of our Ambassador and two former Navy SEALs is more than a "bump in the road," it is a global catastrophe where America is seen as being weak and vulnerable by our enemies. This President has failed to establish a red line for Iran's nuclear ambitions and has failed to recognize the scale and implications of the attacks against us. Reagan had it right: don't negotiate with terrorists and recognize the clear and present danger of not being willing to act or lead from the front.

Zinke has been a frequent critic of President Obama's foreign policy, and started a super PAC, Special Operations for America, that has released ads to that effect, including an ad highlighting Obama's bows to foreign monarchs.

Beyond the political debate, however, Navy SEALs are also a close-knit brotherhood, and do not take kindly to disrespect when lives are lost. President Obama's "bumps in the road" comment is particularly chafing because of the credit he has taken for the success of the SEALs in the raid against Osama bin Laden.

They are heroes when they return, and heroes when they fall--not just when it is politically convenient for those in power.

First an attack in Libya, then an ambush

The U.S. diplomatic compound after it was attacked on Sept. 12 in Benghazi, Libya. The assault on American officials in Libya, set off by a video denigrating the Prophet Muhammad, has transformed into what the Obama administration now, after initial hesitation, describes as a terrorist attack. MOHAMMAD HANNON / ASSOCIATED PRESS, FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

Published: Friday, September 21, 2012 at 1:00 a.m.

Last Modified: Thursday, September 20, 2012 at 10:12 p.m.

WASHINGTON - The survivors of the assault on the U.S. Mission in Benghazi, Libya, thought they were safe. They had retreated to a villa not far from the main building where the surprise attack had occurred, and a State Department team had arrived to evacuate them. The eruption of violence had ended, and now they were surrounded by friendly Libyan brigades in what seemed to be a dark, uneasy calm.

A colleague's body lay on the ground. They had no idea where their boss, the U.S. ambassador, was, nor how in the confusion he had become separated from his bodyguard and left behind.

Then, shortly after 2 a.m. on Sept. 12, just as they were assembling to be taken to the airport, gunfire erupted, followed by the thunderous blasts of falling mortar rounds. Two of the mission's guards -- Tyrone S. Woods and Glen A. Doherty, former members of the Navy SEALs -- were killed just outside the villa's front gate. A mortar round struck the roof of the building where the Americans had scrambled for cover.

The attackers had lain in wait, silently observing as the rescuers, including eight State Department civilians who had just landed at the airport in Benghazi, arrived in large convoys. This second attack was shorter in duration than the first, but more complex and sophisticated.

It was an ambush.

"It was really accurate," Fathi al-Obeidi, commander of special operations for a militia called Libyan Shield, who was there that night, said of the mortar fire. "The people who were shooting at us knew what they were doing."

They also escaped, apparently uninjured.

Interviews with Libyan witnesses and U.S. officials provide new details on the assault on U.S. diplomatic facilities.

Page 2 of 4

The attack has raised questions about the adequacy of security preparations at the two U.S. compounds in Benghazi. Both were temporary homes in a dangerous, insecure city, and were never intended to become permanent diplomatic missions with appropriate security features built into them.

Neither was heavily guarded, and the second house was never intended to be a "safe house," as initial accounts suggested. At no point were the Marines or other U.S. military personnel involved, contrary to news reports early on.

Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton announced on Thursday the creation of a review board led by a veteran diplomat and former undersecretary of state, Thomas R. Pickering. She also briefed lawmakers behind closed doors on Capitol Hill.

But the State Department now faces congressional demands for an independent investigation of the attacks and any security failures that might have added to the death toll.

Investigators and intelligence officials are now focusing on the possibility that the attackers were affiliated with, or possibly members of, al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb -- a branch of the terrorist franchise that originated in Algeria -- or at least in communication with it before or during the initial attack at the mission and the second one at the mission's annex, a half-mile away.

One extremist now under scrutiny is a former detainee at the prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, Abu Sufian Ibrahim Ahmed Hamouda, a Libyan who is a prominent member of an extremist group called Ansar al-Sharia, which some have blamed for the attack.

"It is safe to assume that any significant extremist in eastern Libya is going to be under a lot of scrutiny right now," a U.S. intelligence official said, adding that it was premature to draw any conclusions

Page 3 of 4

The most significant inconsistency between Libyan and U.S. accounts is whether the attack that night began with a small protest over the trailer of "The Innocence of Muslims," parts of which were broadcast on Egyptian television. U.S. officials insist there was a protest that began peacefully, only to be hijacked by armed militants.

But Libyan witnesses, including two guards at the building, say the area around the compound was quiet until the attackers arrived, firing their weapons and storming the compound from three sides, beginning at 9:30 p.m. on Sept. 11. A witness said that some of those attacking referred to the film's insults to Islam.

Matthew Olsen, the director for the National Counterterrorism Center, said at a Senate hearing on Wednesday that the authorities believe "this was an opportunistic attack" that "evolved and escalated over several hours."

What is clear, however, is that those who arrived at the mission -- not officially a consulate, though Libyans call it that informally -- came intending to inflict maximum damage on the building. They quickly overwhelmed a small security detail that included three guards from a force called the 17th of February Brigade and five Libyans employed by a British security company called Blue Mountain.

In a detail not previously disclosed, after storming the compound, the attackers poured diesel fuel around the exterior of the building where Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens; a computer technician, Sean Smith; and a security officer had settled in for the night, and ignited it. It is not clear if they knew anyone was inside.

By that time, according to officials, the three had moved into a part of the building designated as a "safe haven," with fortified doors and no external exposure. The dense, billowing smoke from the fire, however, forced them to leave the haven and head for an exit. It was at that time that they became separated. The security guard, who has not been identified, made it out of the house, but Smith and Stevens did not. Both died of asphyxiation from the smoke.

The guard, now joined by others, found Smith's body, but not the ambassador's. By 11:20 p.m., nearly two hours after the shooting started, they retreated to the mission's second compound, or annex, which had been rented after the fall of Moammar Gadhafi's government last year to provide additional space for a diplomatic team that now included roughly two dozen Americans in all.

The State Department's operations center, now aware of the attack in progress, set in motion a contingency plan drafted for emergencies. A civilian airliner contracted by the department and on standby at Tripoli's airport flew to Benghazi, arriving at 1:30 a.m. with the eight additional security officers.

Al-Obeidi, the commander with the Libya Shield brigade, was ordered to meet them at the airport, take them to the mission's annex and escort them back to the airport to be evacuated. Al-Obeidi expected to find only a few people inside and was surprised to find the entire staff from Benghazi, more than two dozen people. "They told me that there would only be a few, but I saw a big number," he said.

When the second attack began, it lasted only five minutes, "but when you are in that situation, it feels like an hour," he added.

The evacuation to the airport did not begin until dawn, but the plane could not carry everyone. It left behind 11 security officers and the three bodies. Al-Obeidi said that the commander of the local operations center, Mustapha Boshala, then ordered a unit to the hospital to retrieve Stevens' body. Two hours later the State Department's plane returned to carry the last Americans out of Benghazi.

U.S. Officials Knew Libya Attacks Were Work of Al Qaeda Affiliates

Sources say intelligence agencies knew within a day that al Qaeda affiliates were behind the attacks in Benghazi, Libya—they even knew where one of the attackers lived. Eli Lake reports.